Financial Penalties

Chapter 10:

Financial Penalties

Financial Penalties

OVERVIEW (In order of obligation)

| Financial Penalty | Minimum Amount | Maximum Amount | Application | Date Enacted |

| Special Assessment (18 U.S.C. § 3013) | $100 | $100 | All individual defendants found guilty of a felony. | 10/11/1996 |

| Restitution (18 U.S.C. § 2259) | – N/A (prior to 12/7/2018 AVAA)

– $3,000 (after 12/7/2018 AVAA) |

Full amount of victim’s losses (reflecting the defendant’s relative role) | All defendants found guilty of a child pornography offense (18 U.S.C. § 2251(d), 2252, 2252A(a)(1)-(5), 2252A(g)) | 9/13/1994, amended 4/24/1996, 12/7/2018 |

| Special Assessment (18 U.S.C. § 2259A) Result of AVAA. | N/A | $17,000 (convicted under 2252(a)(4) or 2252A(a)(5), $35,000 (trafficking in child pornography), $50,000 (child pornography production) | All defendants found guilty of a child pornography offense. | 12/7/2018 |

| Fine (18 U.S.C. § 3571) | Depends on various factors[1] | $250,000 | All defendants found guilty of a felony. | 10/12/1984, amended 12/11/1987 |

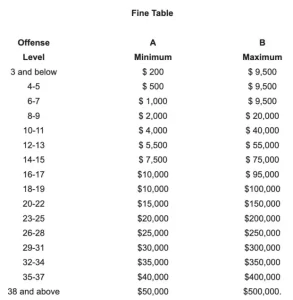

| Guidelines (18 U.S.C. § 5E1.2) | See column A below | See column B below | Recommended fine range based on offense level. | 11/1/1987, amended 1/15/1988, 11/1/1989, 11/1/1990, 11/1/1991, 11/1/1997, 11/1/12002, 1/25/2003, 11/1/2003, 11/1/2011, 11/1/2005 |

| Justice for Victims of Trafficking Act (JVTA) (§ 3014). | $5,000 | $5,000 | Any non-indigent person convicted of an offense under chapter 77 (trafficking), 109A (sexual abuse), 110 (sexual exploitation/abuse of children), 117 (transportation for illegal sexual activity), or 274 (human smuggling). | 5/29/2015 |

| Criminal Forfeiture (18 U.S.C. § 2253) | Visual depictions and related property, proportional to offense | Visual depictions and related property, proportional to offense | People convicted of an offense involving a visual depiction described in § 2251, 2251A, 2252, 2252A, or 2260 or convicted of an offense under § 2252B or chapter 109A. | 5/21/1984, amended 11/18/1988, 11/29/1990, 9/13/1994, 10/30/1998, 7/27/2006 |

Any money received from a defendant shall be disbursed so that each of the following obligations is paid in full in the following sequence: (A) A special assessment under section 3013, (B) Restitution to victims of any child pornography production or trafficking offense that the defendant committed, (C) An assessment under section 2259A, (D) other orders under any other section of title 18, (E) all other fines, penalties, costs, and other payments required under the sentence.[2]

[1] Nature of images (age of children depicted, whether they involved sadistic/masochistic/violence), number of images possessed, computer use, distribution, defendant’s pattern of activity

[2] 18 U.S.C. § 2259A

FINES (18 U.S.C. § 3571, U.S.S.G. 5E1.2)

The Eighth Amendment maintains that a punitive fine must bear some relationship to the gravity of the offense that it is designed to punish. If a fine is grossly disproportionate to the gravity of the offense, it violates the Excessive Fines Clause.[3]

There is a statutory maximum of a $250,000 fine for people found guilty of a felony.[4] If the person derives pecuniary gain from the offense, or if their offense causes pecuniary losses for anyone else, they cannot be fined more than the greater of twice the gross gain or twice the gross loss.[5] If a law that defines a particular offense says there should be no fine or a fine lower than what is generally applicable under § 3571, and explicitly states that the offense is exempt from the usual fine mentioned in § 3571, then the defendant cannot be fined more than the amount specified in the law that defines that particular offense.[6]

The guidelines range for applicable fines is as follows:[7]

When deciding the fine amount, the court must consider the seriousness of the offense, the defendant’s ability to pay, the burden on the defendant and their dependents, restitution or reparation, collateral consequences, prior fines for similar offenses, costs to the government, and equitable considerations. The fine should be enough to ensure that, when combined with other penalties, it serves as a punitive measure.[8] They should not impose a fine that the defendant has little chance of paying.[9] The court does not need to provide detailed findings on each of the factors, but it must consider at least “the factors relevant to the particular case before it.”[10]

Examples of how fines were determined: The Seventh Circuit found that two $200,000 fines for possession and transportation of more than 10 images of child pornography were not disproportionate to the defendant’s crimes because he was a repeat offender, and the fines were less than the maximum $250,000 fine that was statutorily authorized for each offense. This finding was supported by the defendant’s $1.9 million net worth and the loss inflicted on others by his conduct.[11] The Eighth Circuit found a $15,000 fine warranted for a defendant charged with two counts of receiving child pornography when the court considered his income, earning capacity, financial resources, his own projection of his ability to earn money during and following his incarceration, his college education, and his prior employment history.[12]

[3] U.S. Const. amend. VIII

[4] 18 U.S.C. § 3571(b)(3)

[5] 18 U.S.C. § 3571(d)

[6] 18 U.S.C.. § 3571(e)

[7] U.S.S.G. 5E1.2(b)(3)

[8] U.S.S.G. 5E1.2(d)

[9] U.S.S.G. 5E1.2(e)

[10] United States v. Berndt, 86 F.3d 803, 808 (8th Cir. 1996)

[11] United States v. Davis, 859 F.3d 429 (7th Cir. 2017)

[12] United States v. Morais, 670 F.3d 889 (8th Cir. 2012)

SPECIAL ASSESSMENT (18 U.S.C. § 3013, § 3014, § 2259A)

18 U.S.C. § 3013 mandates that the court must assess $100 on anyone convicted of a felony.[13]

18 U.S.C. § 3014 mandates that from the date of enactment of the Justice for Victims of Trafficking Act of 2015 – December 23, 2024, in addition to the assessment imposed under § 3013, the court must assess an amount of $5,000 on any non-indigent person convicted of an offense under chapter 77 (trafficking), 109A (sexual abuse), 110 (sexual exploitation/abuse of children), 117 (transportation for illegal sexual activity), or 274 (human smuggling).[14] This assessment is not payable until the person has satisfied all outstanding-court ordered fines, restitution, and other victim-compensation obligations. Assessments under this section are transferred to the Domestic Trafficking Victims’ Fund.

The Amy, Vicky, and Andy Child Pornography Victim Assistance Act of 2018 (AVAA) created a Child Pornography Victims Reserve Fund within the federal Crime Victims Fund, which is funded by assessments from defendants convicted of child pornography offenses and set-aside funds. 18 U.S.C. § 2259A was created and set maximum amounts defendants can be assessed for based on particular offenses: a court cannot assess more than $17,000 on those convicted under 2252(a)(4) or 2252A(a)(5), $35,000 on those convicted of trafficking in child pornography, and $50,000 on those convicted of child pornography production. These dollar amounts are adjusted annually based on the Consumer Price Index. To determine the amount of assessment, the court is to consider the factors outlined in § 3553(a) and § 3572. Victims of child pornography can elect to receive a one-time payment of $35,000 from this fund instead of fighting for restitution.

[13] 18 U.S.C. § 3013

[14] 18 U.S.C. § 3014

MANDATORY RESTITUTION (18 U.S.C. § 2259)

The Mandatory Victim Restitution Act of 1996, codified in part in 18 U.S.C. § 3363A, requires courts to order defendants to pay victims restitution in certain cases. Child pornography offenses are included in this mandate under 18 U.S.C. § 2259.

Prior to 2018, 18 U.S.C. § 2259 did not specify a minimum amount of restitution and specified that the maximum amount was the full amount of the victim’s losses. The Supreme Court Case Paroline v. United States (2014) called for clarification of the meaning of the restitution statute, and the Amy, Vicky, and Andy Child Pornography Victim Assistance Act of 2018 (AVAA) was subsequently passed. After the passage of the AVAA, § 2259 was modified to require defendants to pay victims a minimum of $3,000 in restitution, as well as clarified the “full amount of the victim’s losses.” The following paragraphs expand upon restitution requirements under § 2259 following the enactment of the AVAA.

18 U.S.C. § 2259 requires the court to order restitution for child pornography production[15] and trafficking in child pornography[16] offenses. The defendant must pay the victim, through the appropriate court mechanism, the full amount of the victim’s losses. The victim is defined as the person harmed as a result of the crime.[17] The full amount of the victim’s losses includes any costs incurred or reasonably projected to be incurred in the future by the victim as a “proximate result” of the offense. The costs include (1) medical services relating to physical, psychiatric, or psychological care, (2) physical and occupational therapy or rehabilitation, (3) necessary transportation, temporary housing, and child care expenses, (4) lost income, (5) reasonable attorneys’ fees, as well as other costs incurred, and (6) any other relevant losses incurred by the victim. Restitution is mandatory, and the court cannot decline to issue an order because of the defendant’s economic circumstances or because the victim is receiving compensation from another source.

In child pornography trafficking cases, the costs include the proximate result of all current or reasonable future costs as a result of trafficking in child pornography depicting the victim. The amount of restitution must reflect the defendant’s “relative role in the causal process that underlies the victim’s losses,” but cannot be less than $3,000. A victim’s total aggregate recovery must not exceed the full amount of their demonstrated losses, so after they received the greatest amount of their losses, the defendant is no longer liable to pay restitution.

Any person who the court determines is a victim of the defendant who was convicted of trafficking in child pornography may choose to receive defined monetary assistance from the Child Pornography Victims Reserve. If so, the court must order payment that is equal to $35,000 until December 7, 2019, and for each year after that, $35,000 multiplied by the ratio of the Consumer Price Index for all Urban Consumers (CPI-U) for the calendar year preceding the calendar year to the CPI-U for the calendar year 2 years before the Dec 7, 2018 – Dec 7, 2019 calendar year.

A victim can obtain defined monetary assistance under the defined monetary assistance subsection only once. However, they are not barred or limited from receiving restitution against any defendant for any offenses not covered by § 2259. If a victim received monetary assistance under this subsection and subsequently sought restitution under § 2259, the court will deduct the amount they received in defined monetary assistance when determining the full amount of the victim’s losses. A victim who has collected payment of restitution under the defined monetary assistance section in an amount greater than the amount provided for under the preceding paragraph is ineligible to receive defined monetary assistance under this subsection.

An attorney representing a victim seeking defined monetary assistance under this subsection may not charge, receive, or collect, and the court may not approve, any payment of fees and costs that in the aggregate exceeds 15% of any payment made under this subsection. Any attorney who does so will be fined under this title, imprisoned not more than one year, or both.

Restitution under 18 U.S.C. § 2259 is mandatory for crimes of production, distribution, receipt, or possession of child pornography with respect to victim status.

[15] § 2251 (a)-(c), § 2251A, § 2252A(g), § 2260(a), or any offense under chapter 109A or 117 that involved the production of child pornography

[16] § 2251(d), § 2252, § 2252A(a)(1)-(5), § 2252A(g) (in cases in which the series of felony violations exclusively involves violations of section § 2251(d), § 2252, § 2252A(a)(1)-(5), or § 2260(b)), or § 3360(b)

[17] If the victim is under 18, incompetent, incapacitated, or deceased: the legal guardian or representative of their estate, another family member, or another suitable person may assume the crime victim’s rights. The defendant cannot qualify as their representative or guardian.

CAUSATION

The Supreme Court found that the proximate cause requirement applies to all of the losses the statute describes requiring an award of restitution for certain federal criminal offenses, including child pornography possession. Restitution under the statute is therefore only proper to the extent that the defendant’s offense is proximately caused by a victim’s losses.[18] (Prior to this 2014 Supreme Court finding, most circuits to have considered the issue interpret the statute as necessitating a proximate causation standard connecting the offense to the losses.[19] Only the Fifth Circuit had found that “proximate causation applies only to the catchall category of harms [in § 2259(b)(3)(F)],” and that the rest of the statute required only “general” causation.[20]) Generally, to say that one event proximately caused another means that the first event caused the latter, and that it was not just any cause, but one with a sufficient connection to the result. An inquiry into whether a former event caused a latter event is an ordinary inquiry into the existence of a causal relation as lay people would view it. Not every cause of an event is proximate, only the ones in which there is a direct relation.[21]

In a case where the defendant’s distribution of the victim’s images began with and was attributable to the defendant, and the victim had ongoing trauma as a result, the Eighth Circuit found that the defendant proximately caused at least some of the victim’s expenses for past and future medical and psychological treatment.[22] Similarly, the First Circuit found that the ongoing shame, humiliation, and helplessness experienced by the victims were the “proximate result” of the defendant’s viewing and distribution of the images.[23]

Determining what constitutes a sufficient chain of causation for determining the losses proximately caused by a defendant’s actions is difficult. The Ninth Circuit offers a helpful framework: a court must identify a causal connection between the defendant’s offense conduct and the victim’s specific losses, and while there may be “multiple links in the causal chain,” the chain “may not extend so far, in terms of the facts or the time span, as to become unreasonable.”[24] For example, the Ninth Circuit held that a defendant’s participation in the audience of people who viewed images of the victim was insufficient to warrant restitution when the government failed to show proximate cause for any particular losses.[25] This differs from an Eleventh Circuit case in which the government established proximate cause through evidence that the victim was notified that the defendant possessed her image, she suffered when she received such notices, and this suffering necessitated further therapy.[26] Thus, there must be evidence of a reasonable “chain” that links a defendant’s action to harm suffered by the victim.

Similarly, the Tenth Circuit found that the proximate cause requirement was not satisfied when the defendant was required to pay a large sum beyond attorney fees after merely viewing images of the victim, making evidence that the defendant was specifically responsible for the victim’s losses “relatively thin.”[27] The Seventh, Fourth, First, Second, D.C., and Eleventh Circuits reached similar conclusions regarding the specificity required to be proven to reach a proximate cause determination.[28]

[18] United States v. Aumais, 656 F.3d 147 (2d Cir. 2011)

[19] United States v. Evers, 669 F.3d 645, 657 (6th Cir. 2012); United States v. McGarity, 669 F.3d 1218, 1268 (11th Cir. 2012); United States v. Aumais, 656 F.3d 147, 152 (2d Cir. 2011); United States v. Kennedy, 643 F.3d 1251, 1261 (9th Cir. 2011); United States v. Monzel, 641 F.3d 528, 536 (D.C. Cir. 2011); United States v. McDaniel, 631 F.3d 1204, 1208 (11th Cir. 2011); United States v. Crandon, 173 F.3d 122, 125 (3d Cir. 1999)

[20] In re Amy Unknown, 636 F.3d 190 (5th Cir. 2011), on reh’g en banc sub nom. In re Unknown, 697 F.3d 306 (5th Cir. 2012), opinion withdrawn and superseded on reh’g en banc sub nom. In re Amy Unknown, 701 F.3d 749 (5th Cir. 2012), vacated and remanded sub nom. Paroline v. United States, 572 U.S. 434, 134 S. Ct. 1710, 188 L. Ed. 2d 714 (2014), and cert. granted, judgment vacated sub nom. Wright v. United States, 572 U.S. 1083, 134 S. Ct. 1933, 188 L. Ed. 2d 955 (2014)

[21] Paroline v. United States, 572 U.S. 434, 134 S. Ct. 1710, 188 L. Ed. 2d 714 (2014)

[22] United States v. Hoskins, 876 F.3d 942 (8th Cir. 2017)

[23] United States v. Chiaradio, 684 F.3d 265, 284 (1st Cir. 2012)

[24] United States v. Kennedy, 643 F.3d 1251, 1262 (9th Cir. 2011); United States v. Peterson, 538 F.3d 1064 (9th Cir. 2008); United States v. Gamma Tech Indus., Inc., 265 F.3d 917, 928 (9th Cir. 2001)

[25] United States v. Kennedy, 643 F.3d 1251 (9th Cir. 2011)

[26] United States v. McDaniel, 631 F.3d 1204, 1207 (11th Cir. 2011)

[27] United States v. Benoit, 713 F.3d 1, 21 (10th Cir. 2013)

[28] United States v. Laraneta, 700 F.3d 983 (7th Cir. 2012); United States v. Burgess, 684 F.3d 445 (4th Cir. 2012), writ denied sub nom. Burgess v. Att’y Gen. of U.S., No. 1:09-CR-00017-GCM, 2014 WL 1432042 (W.D.N.C. Apr. 14, 2014); United States v. Kearney, 672 F.3d 81 (1st Cir. 2012); United States v. Aumais, 656 F.3d 147 (2d Cir. 2011); United States v. Monzel, 641 F.3d 528 (D.C. Cir. 2011); United States v. McDaniel, 631 F.3d 1204 (11th Cir. 2011)

DETERMINING RESTITUTION

The Supreme Court found that restitution for child pornography possession, when the defendant both possessed a victim’s images and the victim had outstanding losses caused by their continuing traffic but it is impossible to trace a particular amount of those losses to the individual, should be awarded in an amount that comports with the defendant’s relative role in the causal process that underlies the victim’s general losses. The court must use the available evidence to assess the significance of the defendant’s conduct in light of the broader causal process that led to the victim’s losses, which is not a precise mathematical inquiry but involves the use of discretion and sound judgment. As a starting point, courts coils determine the among of the victim’s losses caused by the continuing traffic in their images, then award restitution after considering the factors that bear on the relative causal significance of the defendant’s conduct in producing those losses. Such factors could include: the number of past defendants found to have contributed to the victim’s general losses, reasonable predictions of the number of future offenders likely to be caught and convinced for crimes contributing to the victim’s general losses, any available and reasonably reliable estimate of the broader number of offenders involved, whether the defendant reproduced or distributed images of the victim, whether the defendant had any connection to the images’ initial production, how many images of the victim that the defendant possessed, and other facts relevant to the defendant’s relative causal role. A defendant cannot be held liable for an amount drastically out of proportion to their individual causal relation to the victim’s losses.[29]

The factors outlined in Paroline are meant to guide the sentencing court’s wide discretion and sound judgment, and are not a mandatory checklist or rigid formula. Other factors often include the frequency of views and shares, the means by which the images were acquired, any stalking or attempts at contacting the victim, the defendant’s individual contribution to the market for the victim’s image over time (e.x. Whether they sought out this particular victim’s images, the length of their involvement in child pornography, whether they displayed a pattern of offenses, and whether they have distributed other images), and the use of images to groom other children for abuse or exposure to pornography.[30]

When a particular loss amount is not determined, including cases when the victim does not participate, the mandatory minimum $3,000 restitution is awarded.[31]

The Seventh Circuit found that it was proper to rely on the calculation of restitution from the defendant’s husband’s sentencing to determine the amount that the defendant owed following her conviction for possession of child pornography.[32]

The D.C. Circuit found that there is no discrete, readily definable incremental loss that can easily be traced to each individual possessor’s exploitation of a child’s pornographic image, so there can be no precise algorithm for computing individual restitution awards. The calculation of the defendant’s relative share of restitution should not be severe, but also should not be token or nominal.[33] Thus, they found a $7,500 award in restitution from a defendant who possessed a victim’s child pornography image was reasonable.

The Fifth Circuit found that a total $50,317 award in restitution was warranted for a defendant convicted of possessing pornographic media of prepubescent minors or minors under 12 due to various factors bearing on the causal significance of the defendant’s conduct in producing victims’ losses. The court used a formula based on the case’s specific factors to determine the maximum amount of restitution victims would be awarded, using the lowest amount requested by a victim as the baseline and adding money based on the number of images of that specific victim.[34] Other courts that used formulas based on case-specific factors to calculate the amount of restitution awarded to each victim were also upheld by various circuits.[35] Such calculations must be based on disaggregate losses, including ongoing losses, caused by the original abuse of the victim from the ongoing distribution and possession of images of that original abuse, to the extent possible.[36]

The Tenth Circuit clarified that the court can only order restitution for losses that the defendant directly caused. If the amount for restitution does not have clear proof that it comes from the harm caused by sharing the images, separate from the original harm to the victim, it is disproportionate.[37]

[29] Paroline v. United States, 572 U.S. 434, 134 S. Ct. 1710, 188 L. Ed. 2d 714 (2014)

[30] United States v. Monzel, 930 F.3d 470 (D.C. Cir. 2019)

[31] United States v. Mobasseri, 828 F. App’x 278 (6th Cir. 2020) (Unreported); United States v. Clemens, 990 F.3d 1127 (8th Cir. 2021)

[32] United States v. Geary, 952 F.3d 911 (7th Cir. 2020)

[33] United States v. Monzel, 930 F.3d 470 (D.C. Cir. 2019)

[34] United States v. Halverson, 897 F.3d 645, 653 (5th Cir. 2018)

[35] United States v. Sainz, 827 F.3d 602 (7th Cir. 2016); United States v. Beckmann, 786 F.3d 672 (8th Cir. 2015); United States v. Rogers, 758 F.3d 37 (1st Cir. 2014)

[36] United States v. Galan, 804 F.3d 1287 (9th Cir. 2015)

[37] United States v. Dunn, 777 F.3d 1171 (10th Cir. 2015)

COSTS

The Supreme Court found that words like “investigation” and “proceedings” in the Mandatory Victims Restitution Act (MVRA) provision requiring reimbursement for expenses incurred during participation in the investigation or prosecution of the offense, or attendance at proceedings related to the offense, were limited to government investigations and criminal proceedings. MVRA therefore does not cover the costs of private investigations that private parties chose to conduct prior to government investigation, even if they later share the information the private investigation uncovered with the government.[38]

The government bears the burden of proving the amount of loss the victim sustained as a result of the defendant’s offense by a preponderance of the evidence.[39] While the amount does not need to be exact, it must be reasonable. Most Circuits have held that restitution for future expenses, including therapeutic costs, is appropriate under the statute as long as the award is based on a reasonable estimate of those costs.[40] If this is the case, they are permitted a present award of restitution for those future losses, otherwise they may seek additional restitution at a later date when the losses are ascertainable (in many cases, the order of restitution for future losses may be inappropriate because they are too difficult to confirm or calculate).[41]

The Fifth Circuit found that where the defendant’s offense caused the need for the victim’s request for restitution to cover expert expenses, restitution was warranted, even though the government did not provide evidence about the victim’s restitution awards in other cases. There was no indication that the victim had received duplicative recovery on their expert expenses.[42]

In determining the amount of restitution for medical expenses, the Eighth Circuit found on multiple occasions that when testimony and a basic knowledge of medical expenses supported a reasonable amount for the type of medical and psychological treatment the victim needed, even though the victim did not document each expense, it was reasonable.[43]

[38] Lagos v. United States, 138 S. Ct. 1684, 201 L. Ed. 2d 1 (2018)

[39] United States v. Baldwin, 774 F.3d 711 (11th Cir. 2014)

[40] United States v. Osman, 853 F.3d 1184, 1190 (11th Cir. 2017); United States v. Rogers, 758 F.3d 37, 39 (1st Cir. 2014); United States v. Pearson, 570 F.3d 480, 486 (2d Cir. 2009); United States v. Danser, 270 F.3d 451, 455 (7th Cir. 2001); United States v. Julian, 242 F.3d 1245, 1246 (10th Cir. 2001); United States v. Laney, 189 F.3d 954, 966 (9th Cir. 1999); United States v. Funke, 846 F.3d 998 (8th Cir. 2017); United States v. Pearson, 570 F.3d 480 (2d Cir. 2009)

[41] United States v. Laney, 189 F.3d 954 (9th Cir. 1999)

[42] United States v. Leal, 933 F.3d 426 (5th Cir. 2019)

[43] United States v. Emmert, 825 F.3d 906 (8th Cir. 2016); United States v. Hoskins, 876 F.3d 942 (8th Cir. 2017)

VICTIM

The Fifth Circuit found that all identified victims were entitled to statutory restitution, and not simply those specifically described in the indictment, when the images described in the indictment were merely examples of images found on the defendant’s cellphone as a whole rather than the sole basis of his charge for possession of child pornography.[44]

The Second Circuit found that a defendant who distributed images of a minor’s sexual abuse “harmed” the minor, because the pornography could haunt the minor in the future, making the minor a “victim” for purposes of restitution eligibility under the Mandatory Restitution for Sexual Exploitation of Children Act.[45] The Eleventh Circuit found that a defendant who possessed child pornography “harmed” a minor in one of the images, making them a “victim” for restitution purposes, because “end users of child pornography enable and support the continued production of child pornography,” providing “the economic incentive for the creation and distribution of the pornography” and violating the minor’s privacy by possessing their image.[46] However, they later clarified that for proximate cause to exist, there must be a causal connection between the actions of the end-user and the harm suffered by the victim, making restitution warranted in some but not all child pornography possession cases.[47]

[44] United States v. Bopp, 79 F.4th 567 (5th Cir. 2023)

[45] United States v. Aumais, 656 F.3d 147, 152 (2d Cir. 2011)

[46] United States v. McDaniel, 631 F.3d 1204, 1208 (11th Cir. 2011)

[47] United States v. McGarity, 669 F.3d 1218, 1269 (11th Cir. 2012)

REMAND

The Fourth Circuit found that when the district court believed the government’s proposed restitution awards were too high, they should adjust the amount and explain its reasoning rather than refuse to order any amount of restitution.[48]

The Fifth Circuit found that ordering $10,000 restitution for the defendant’s offense of sexual exploitation of a child, while also recording victims’ losses as $0.00, lacked support and is therefore unwarranted, as the government did not present evidence of the specific losses for the victim’s therapy sessions or her parent’s time off from work. Similarly, the Second Circuit found that when the court did not explain how it estimated the victims’ future expenses when awarding full restitution, it could not determine whether the final amount reflected a reasonable estimate of future counseling.[49]

[48] United States v. Dillard, 891 F.3d 151 (4th Cir. 2018)

[49] United States v. Pearson, 570 F.3d 480 (2d Cir. 2009)

18 U.S.C. § 2253: CRIMINAL FORFEITURE

STATUTE

People convicted of an offense involving a visual depiction described in § 2251, 2251A, 2252, 2252A, or 2260 or convicted of an offense under § 2252B or chapter 109A, must forfeit to the United States their interest in:

- Any visual depiction described in § 2251, 2251A, 2252, 2252A, 2252B, or 2260, or any book, magazine, periodical, film, videotape, or other matter containing any such visual depiction, which was produced, transported, mailed, shipped, or received in violation of this chapter;[50]

- Any real or personal property constituting or traceable to gross profits or other proceeds obtained from such offense; and

- Any real or personal property used or intended to be used to commit or to promote the commission of such offense, or any property traceable to such property.

Section 413 of the Controlled Substances Act (21 U.S.C. 853), with the exception of subsections (a) and (d), applies to the criminal forfeiture of property pursuant to subsection (a).

[50] Title 18 Part I Chapter 110

USE

Many circuits employ the ordinary meaning of “use,” which is “‘[t]o convert to one’s service,’ ‘to avail oneself of,’ and ‘to carry out a purpose or action by means of.’”[51]

[51] Bailey v. United States, 516 U.S. 137, 116 S. Ct. 501, 133 L. Ed. 2d 472 (1995); Smith v. United States, 508 U.S. 223, 113 S. Ct. 2050, 124 L. Ed. 2d 138 (1993)

ENFORCEMENT

§ 2253(a)’s forfeiture provisions are mandatory, and thus courts cannot deny forfeiture no matter the circumstances. The Fourth Circuit clarifies that “[t]he plain text of the statute thus indicates that forfeiture is not a discretionary element of the sentencing,” even in light of equitable considerations.[52]

[52] United States v. Blackman, 746 F.3d 137, 143 (4th Cir. 2014)

EXCESSIVE FINES

The principle of proportionality found in the Excessive Fines Clause of the Eighth Amendment requires that the amount of forfeiture must bear some relationship to the gravity of the offense that it is designed to punish. If a forfeiture is grossly disproportionate to the gravity of the defendant’s offense, it is unconstitutional.[53]

The Eighth Circuit found that forfeiture of a defendant’s property was not disproportionate to the gravity of his child pornography offenses when his actions warranted the maximum fine of $200,000 and his equity in property was $192,632.[54]

[53] U.S. Const. amend. VIII

[54] United States v. Hull, 606 F.3d 524 (8th Cir. 2010)

PROPERTY

Many circuits agree that the government must show a substantial connection between real property and the child pornography offenses, although the property does not need to be “indispensable” to the crimes.[55]

The Eighth Circuit found that the defendant’s house and 19 surrounding acres of rural land, because he used a computer room in his house to connect to the Internet and distribute child pornography from there, constituted property warranting of forfeiture. The surrounding acreage was included because the defendant purchased it in one land contract.[56] Similarly, the Third Circuit found that a forfeiture order for the defendant’s computers included all files and programs on the computers, as “any property” does not indicate only a portion of the property.[57]

Owners of cryptocurrency accounts who used or intended to use them to commit or to promote the commission of child pornography offenses warrants the forfeiture of the accounts.[58]

The Fourth Circuit clarified that the government bears the burden of “establish[ing] a nexus between the property for which it is seeking forfeiture and the crime by a preponderance of the evidence.”[59] In that light, the Seventh Circuit held that generally, for property to be forfeited, a jury must specifically determine that the government established the requisite nexus between the property and the defense, and return a special verdict form reflecting that finding.[60]

In child pornography cases, non-contraband files stored on contraband electronic devices must be forfeited along with the devices themselves.[61]

[55] United States v. Premises Known as 3639-2nd St., N.E., Minneapolis, Minn., 869 F.2d 1093, 1096 (8th Cir. 1989); United States v. Herder, 594 F.3d 352, 364 (4th Cir. 2010)

[56] United States v. Hull, 606 F.3d 524 (8th Cir. 2010)

[57] United States v. Noyes, 557 F. App’x 125, 127 (3d Cir. 2014) (Unpublished)

[58] United States v. Twenty-Four Cryptocurrency Accts., 473 F. Supp. 3d 1 (D.D.C. 2020)

[59] United States v. Martin, 662 F.3d 301, 307 (4th Cir. 2011)

[60] United States v. Ryan, 885 F.3d 449 (7th Cir. 2018)

[61] United States v. Noyes, 557 F. App’x 125 (3d Cir. 2014) (unpublished); United States v. Wernick, 673 F. App’x 21, 25 (2d Cir. 2016) (unpublished); United States v. Sanders, 622 F. Supp. 3d 223, 230 (E.D. Va. 2022)

DUE PROCESS

The Ninth Circuit held that a defendant’s due process rights were not violated by a forfeiture order when he was provided notice in the indictment and the judgment of conviction.[62]

[62] 132 Fed.Appx. 130, 2005 WL 1127082 (C.A.9 (Mont.))(Unpublished)